Remember the Ladies: Marking the Places where Huntsville Women Made History

On the centennial anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment, the Historic Huntsville Foundation, the Twickenham Town Chapter of the DAR, and the Councill High School Alumni Association are creating a lasting tribute to Huntsville’s pantheon of suffrage heroes through four historic markers that recognize the Black and white Huntsville women whose fight for equal suffrage shaped the future of our nation. These markers will ensure that the stories of the leaders of the Huntsville Equal Suffrage Association (HESA) and the six Black Madison County women who successfully registered to vote in 1920 are permanently inscribed in the Huntsville landscape.

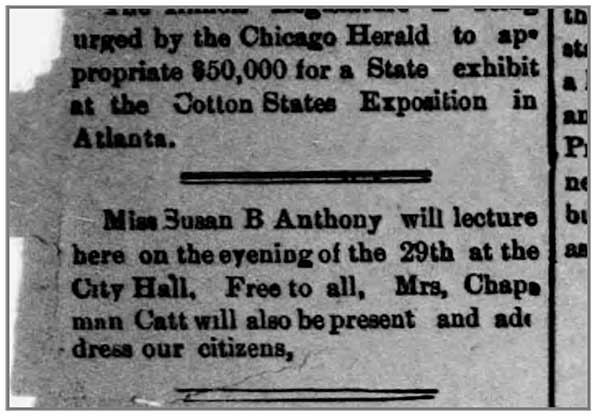

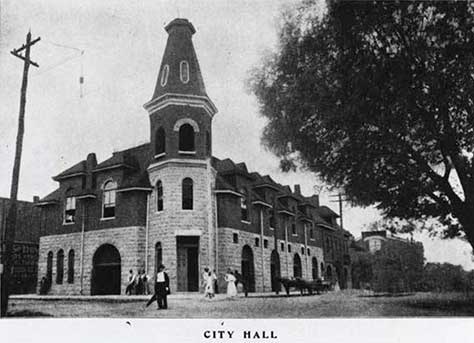

Did you know? After Anthony and Catt spoke at the Huntsville City Hall in 1895, they celebrated with a grand party at Abingdon, the estate of Ellelee Chapman and Milton Humes, located on Meridian Street. The house was demolished in the 1960s.

Huntsville’s suffrage movement began in 1895, when Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt spoke to an overflow crowd in Huntsville’s City Hall. The women accepted the invitation of Alberta Chapman Taylor, a daughter of Alabama governor Reuban Chapman. After Anthony spoke, Milton Humes stepped forward and declared the creation of HESA. Many of the city’s most prominent men and women lined up to join. Knowing their attendance would violate Huntsville’s color line, no Black men or women attended the meeting. But Black women clearly understood the importance of women’s suffrage and how voting rights could benefit themselves and their community.

The white women who led HESA were philanthropic and worked for the betterment of their community. They founded the City Infirmary, the forerunner of Huntsville Hospital. They supported the public library and funded literacy campaigns. They wanted better schools, health and sanitation reforms, and workplace reforms to keep children from textile mills and coal mines. Their prejudice, however, blinded them to the injustices caused by racial inequality.

The majority of Alabamians opposed women’s suffrage in 1895. They believed politics was the domain of men, and that women had privileged status as wives and mothers and should not involve themselves in political matters. Suffragists adopted an incremental approach to women’s rights and lobbied the Alabama legislature for laws that gave women more control over their bodies and property. In 1900, the Alabama Legislature passed laws that allowed women to will their estate to whomever they wished and have a bank account in their own name. The Legislature also raised the age of consent for women, or girls, from 10 to 14 years of age, a bill they had refused to approve in previous sessions.

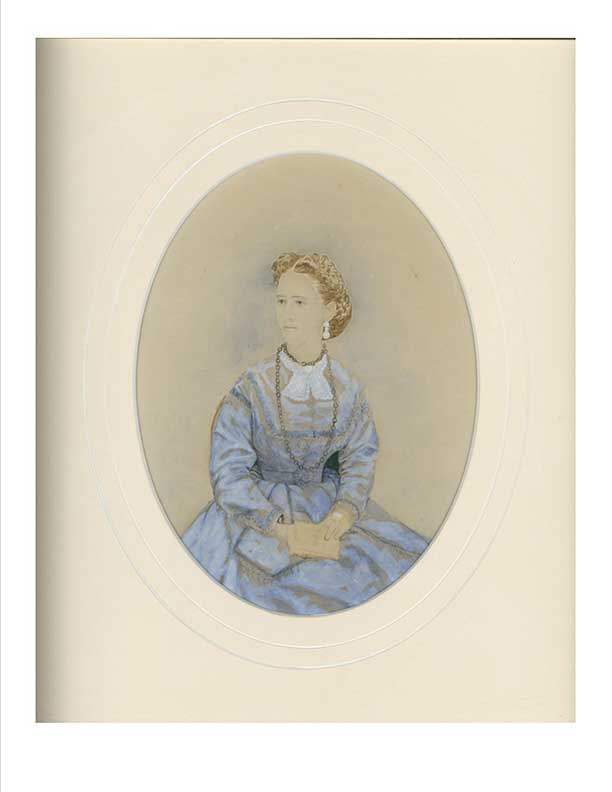

Interest in women’s suffrage lagged until around 1912, when success at the national level energized Alabama’s local suffrage groups. HESA reconvened and members faced an immediate challenge finding a regular meeting place. Members hoped to meet at the Greene Street YMCA, as HESA members regularly donated to the YMCA. The YMCA denied their request, stating that women’s suffrage was too controversial. Ellelee Humes, HESA Vice President, volunteered her McClung Avenue house for meetings.

Coordinated lobbying by suffragists led Alabama lawmakers to pass a bill in 1915 allowing women to run for county school board seats. The following year, ten Alabama women announced their candidacy. Six won, including Huntsville resident Alice Boarman Baldridge who won a seat on the Madison County School board—four years before women had the right to vote. Two years later, at the age of 44, Baldridge passed the Alabama Bar Exam and became Madison County’s first female practicing attorney.

After the ratification of the 19th amendment in August 1920, Alabama officials began registering qualified women to vote for the upcoming 1920 presidential election. Within two months, 123,000 Alabama women registered, including 1,383 from Madison County, of whom six were Black. Fewer than 200 Black women qualified to register in Alabama.

In the decades following the ratification of the 19th amendment, the votes of Black and white Alabama women helped establish Alabama’s Child Welfare Department, increase appropriations to the Public Health Department, increase the education budget, end the convict labor lease system, and elect the first woman to the Alabama Legislature in 1922.

Integrating the stories of Huntsville women into our public history through historic markers enhances Huntsville’s reputation of distinctiveness. Huntsville is strong enough to tell the difficult chapters of our history with honesty and empathy, so we can celebrate the progress we have made together.

Did you know??? More Alabama women registered to vote in 1920 than any other southern state.

Donna Castellano is the Executive Director of the Historic Huntsville Foundation.